While global agribusiness giants such as Monsanto, Cargill, Bayer and DuPont are best known for their control over the global seeds, cereals and agrochemicals market, symbolizing the corporate takeover of the food system, an extremely powerful segment of agribusiness remains hidden from public scrutiny: The companies that control the production, processing and trade of beef, poultry and pork worldwide. This is because they often hide behind a “brand” name for their products and because their end product (meat) does not appear directly responsible for the negative impacts of the supply chain. Last November, IATP published research showing that the top 20 meat and dairy companies, known as the “Meat Majors,” produce more greenhouse gases than Germany. Even if the world were to eliminate the use of fossil fuels, unless over consumption of meat is eliminated and reduced to sustainable levels, the Earth is likely to face more than 2 degrees of global warming by 2050.

IATP defines the “Global Meat Complex” as a highly concentrated (horizontally and vertically), integrated web of transnational corporations (TNCs) that controls the inputs, production and processing of mass quantities of food animals. Some of these TNCs occupy all major parts of the global meat production value chain. For instance, Cargill is one of the world’s leading grain traders, supplying grains for feed; the second-largest feed manufacturer in the world; and the third-largest meat processor (in food sales) in the world. Others, like Thailand’s CP Group, China’s New Hope Liuhe and Wen’s Food Group or Brazil’s BRF are the world’s leading feed manufacturers and meat processing giants in their own right.

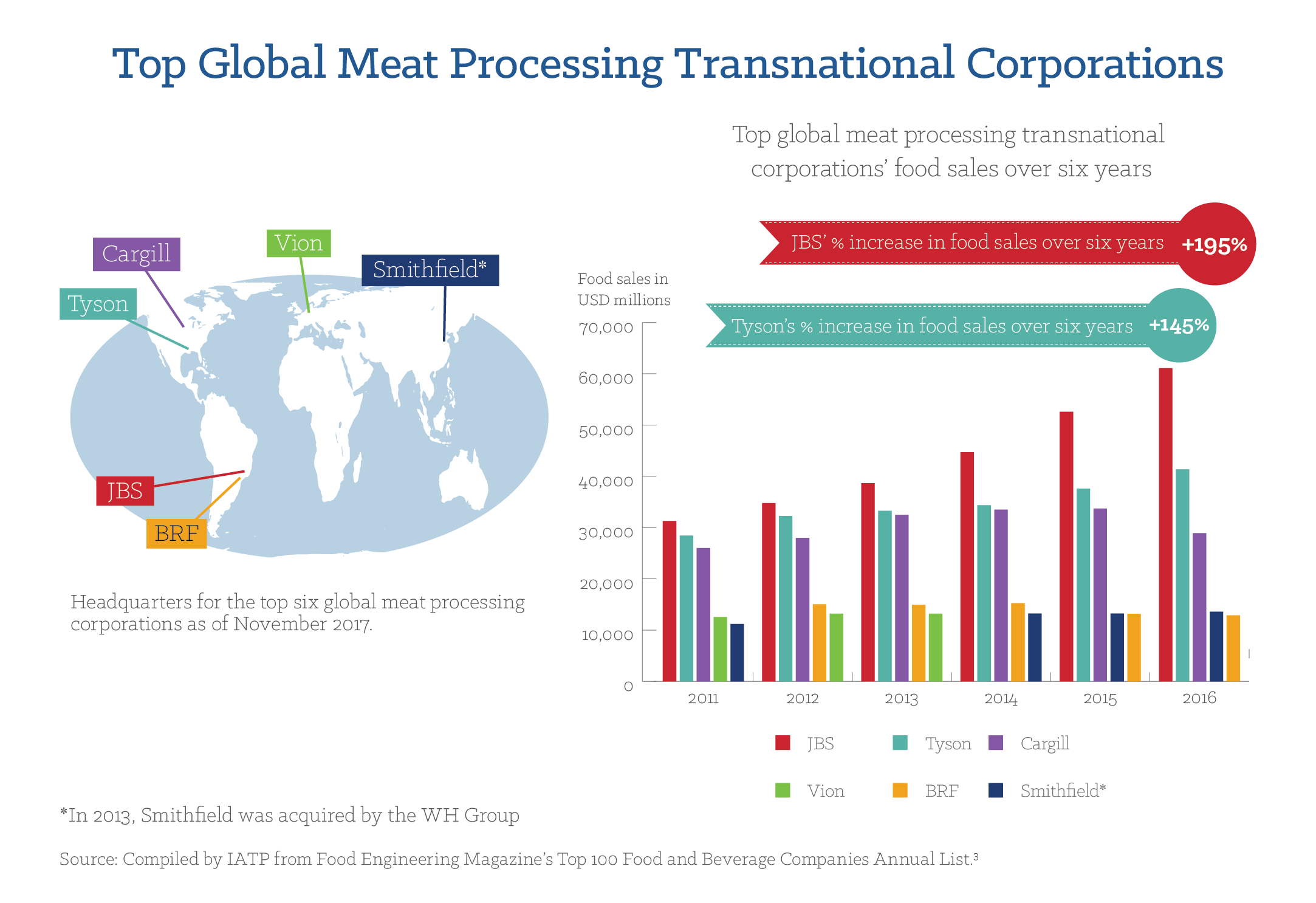

The rise of this type of agribusiness has been phenomenal over the last forty years, but particularly intense since the 2000s. JBS, Tyson Foods, Cargill and Smithfield are the world’s largest meat-producing corporations. JBS alone accounted for over ten million tons (carcass weight equivalent) of meat processing in 2009-2010, surpassing the combined total of the world’s top 11 to 20 companies. Each of these companies has deployed a mix of similar main strategies: Mergers and acquisitions of other companies, vertical integration of their supply chains (including product diversification and/or wholesale retail), and successful lobbying of governments that in turn negotiate trade and investment deals that ease these companies’ access to foreign markets.

The Global Picture

The sheer power of these companies obscures the fact that only 9.7 percent of the meat produced in the world is traded. Much of it is grown by small producers and stays within the region.

However, the top ten global meatpackers still dominate the whole sector. And, even among them, the top three (JBS, Tyson Foods and Cargill) have food sales that are double or triple that of number 4, Smithfield Foods (now owned by Chinese WH Group) and number 5, BRF (formerly known as Brasil Foods). This concentration in buyers puts pressure on farmers to accept lower prices, while conforming to evermore burdensome requirements from the companies for what animals to raise and how to raise them.

The phenomenal rise of these giants has been achieved with the explicit support of public funds from governments, through policies that allow these corporations to pollute land and water, and by governments absorbing the public health costs and risks generated by this industry. For instance, nearly 40 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa and North America have faced a new wave of highly-pathogenic bird flu since October 2016. It is decimating both wild and farmed bird populations—not only costing farmers and the public millions of dollars in mitigation, but, more importantly, increasing the risk of transfer to humans that has led to deaths in countries like China. In the US, dairy Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) from Iowa to Alabama are receiving tax breaks and subsidies while also being exempted from reporting their GhG emissions.

Despite the evidence that these companies are major contributors to climate change, they are not being held accountable for their emissions in any consistent way, leading with green-washed PR strategies. Cargill, for example, has set a goal of 5 percent reduction in emissions intensity by 2020. However, reducing the intensity of emissions could be completely offset by their continued growth, leading to an increase in overall emissions. Our forthcoming report aims to debunk these claims of sustainability so that we can begin to hold the Meat Majors accountable. It is clear that the future of a healthy food system depends on reigning in the power of these mighty giants.

If you’ve enjoyed this article and others like it, please consider making a contribution to support our work today. As a nonprofit, we rely on the generosity of our supporters to provide high-level research and analysis on agriculture and trade policy.