Introduction

The effects of climate change are increasingly apparent—2016 was recorded as the hottest year ever, and droughts, floods, wildfires and other extreme weather events are rising globally. The implications of these changes are tremendous; yet, the United States does not currently have a national plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2015, the Obama Administration presented the Clean Power Plan as the first nationwide policy to address climate change. The plan aimed to reduce electricity sector emissions to 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 by reducing emissions from existing coal fired power plants.1 Each state was given an emissions reduction target and great flexibility in choosing how to meet that target. While the Clean Power Plan was significant in that it was the first federal climate change policy, it only covered coal-fired power plant emissions and left out other high emitting sectors of the economy, including transportation, infrastructure and housing. Furthermore, it encouraged states to create and join in regional carbon markets, which have proven ineffective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions for reasons this paper will address.

After a series of legal challenges and President Trump’s Executive Order to dismantle the rule, the Clean Power Plan will no longer go into effect. It is highly unlikely that the federal government will pursue action on climate change anytime soon. The Trump administration’s cabinet is filled with varying levels of climate deniers, including former Exxon/Mobil CEO and now Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who has stated that climate science was “inconclusive;” head of the Environmental Protection Agency Scott Pruitt, who has denied the scientific consensus on human contributions to climate change; and Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, who wrote that those calling for climate action are “so obviously disconnected from reality.” In addition, President Trump’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2018 recommends slashing the Environmental Protection Agency’s budget by over 30 percent and closing the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Justice, which is instrumental in ensuring equitable environmental policy. Perhaps most notably, President Trump announced that he is pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, sending a signal to the world that the U.S. federal government will not act on climate change.

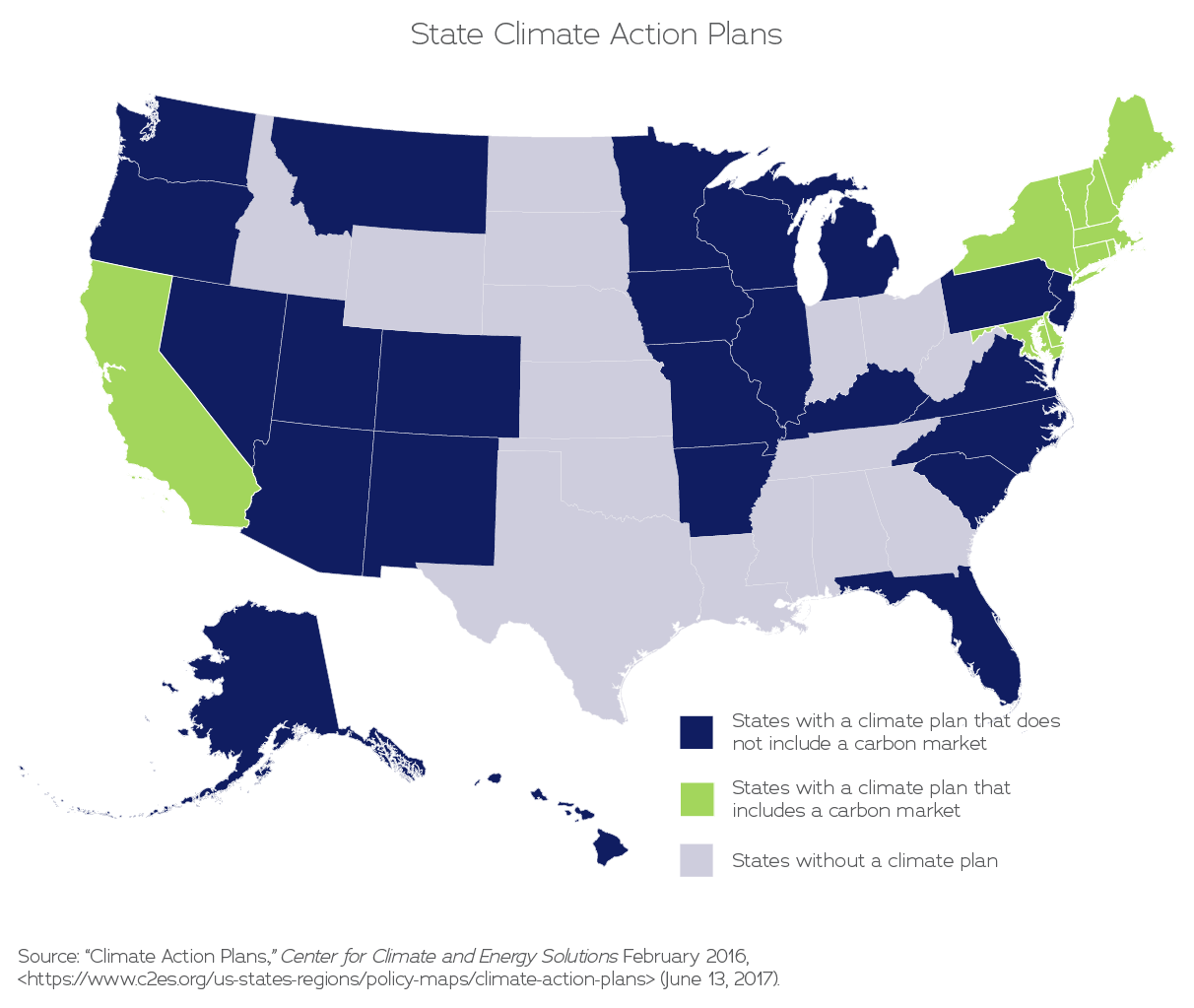

As the federal government moves backwards on climate action, there are new opportunities for states to take the lead. The end of the Clean Power Plan creates an opportunity to reset thinking on climate policy, learn from past mistakes and expand progress on what has been working. Currently, 34 states plus Washington D.C. have some form of climate action plan,2 but there’s significant room for them to be strengthened and for more to be created.

Since the 2016 presidential election, several states have already announced their own climate change initiatives. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced an initiative in May 2017 to curb the state’s methane emissions—one of the first such initiatives in the country. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe issued an Executive Order in the same month directing the state to begin creating a carbon market. This is unsurprising given that carbon markets are the default for many at the state level when thinking about climate policy, but enthusiasm for carbon markets is surprising given this approach’s poor track record. They rarely lead to real, sustainable greenhouse gas emissions reductions and can harm the health and economic security of communities in the process. Historically, rural communities, low-income communities and communities of color have been disproportionately harmed by polluters operating within carbon markets, making them an inequitable choice for climate action.

Instead of using the lack of federal climate change policy as a catalyst to create more carbon markets, states should consider policies that combine effective, predictable regulation with investment in climate friendly energy and infrastructure. Rural, low-income and minority communities can benefit greatly from investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency, from increased jobs in the clean energy sector and from local ownership that retains wealth in the community. Such policies best arise from deep community engagement and inclusive processes that strive to address local concerns so that communities can remain resilient as they adapt to climate change. This paper will outline why carbon markets will not work to address the climate crisis and provide recommendations for states to consider as they create their own climate change plans.