Introduction: Brazil’s Rise to the Top of the Global Meat Complex

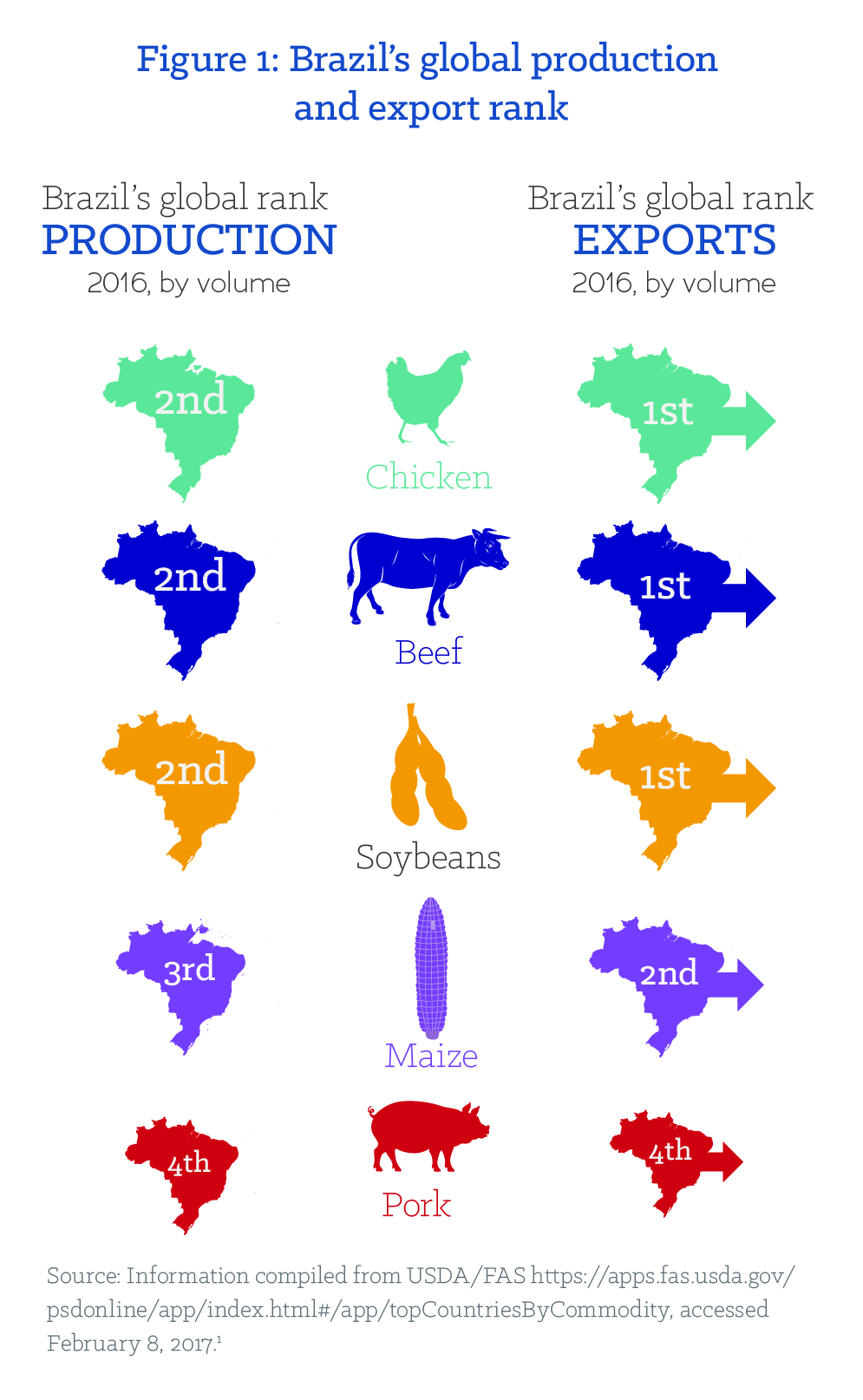

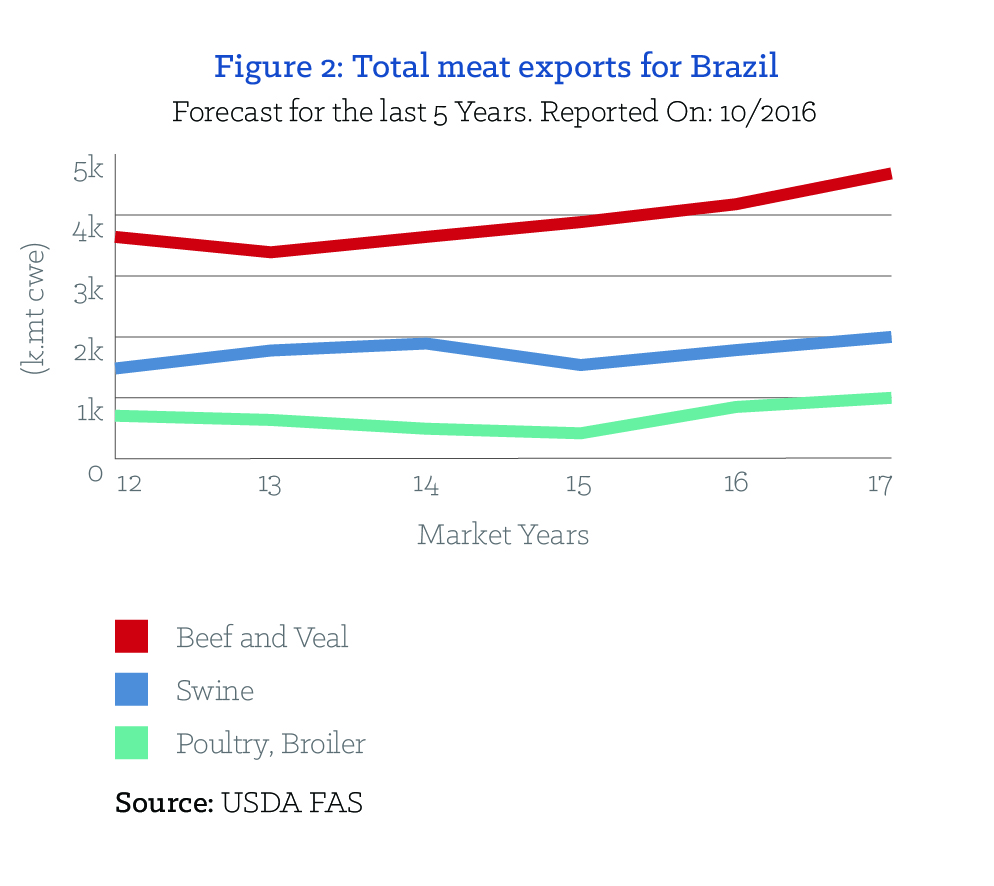

Brazil is the world’s leading exporter of soybeans; the second largest exporter of maize; and the world’s largest beef trader, exporting more than 20 percent of the world’s beef (Figures 1 and 2). It has overtaken the United States to become the biggest exporter of poultry in the world, close to 39 percent of total global exports. With China drastically increasing its pork imports in the last two years, Brazil has also stepped in to meet this demand. The massive expansion in production has had dramatic impacts on Brazilians linked to the supply chain and on Brazil’s prized environment, and has additionally made Brazil increasingly dependent on these commodities to maintain a trade surplus.

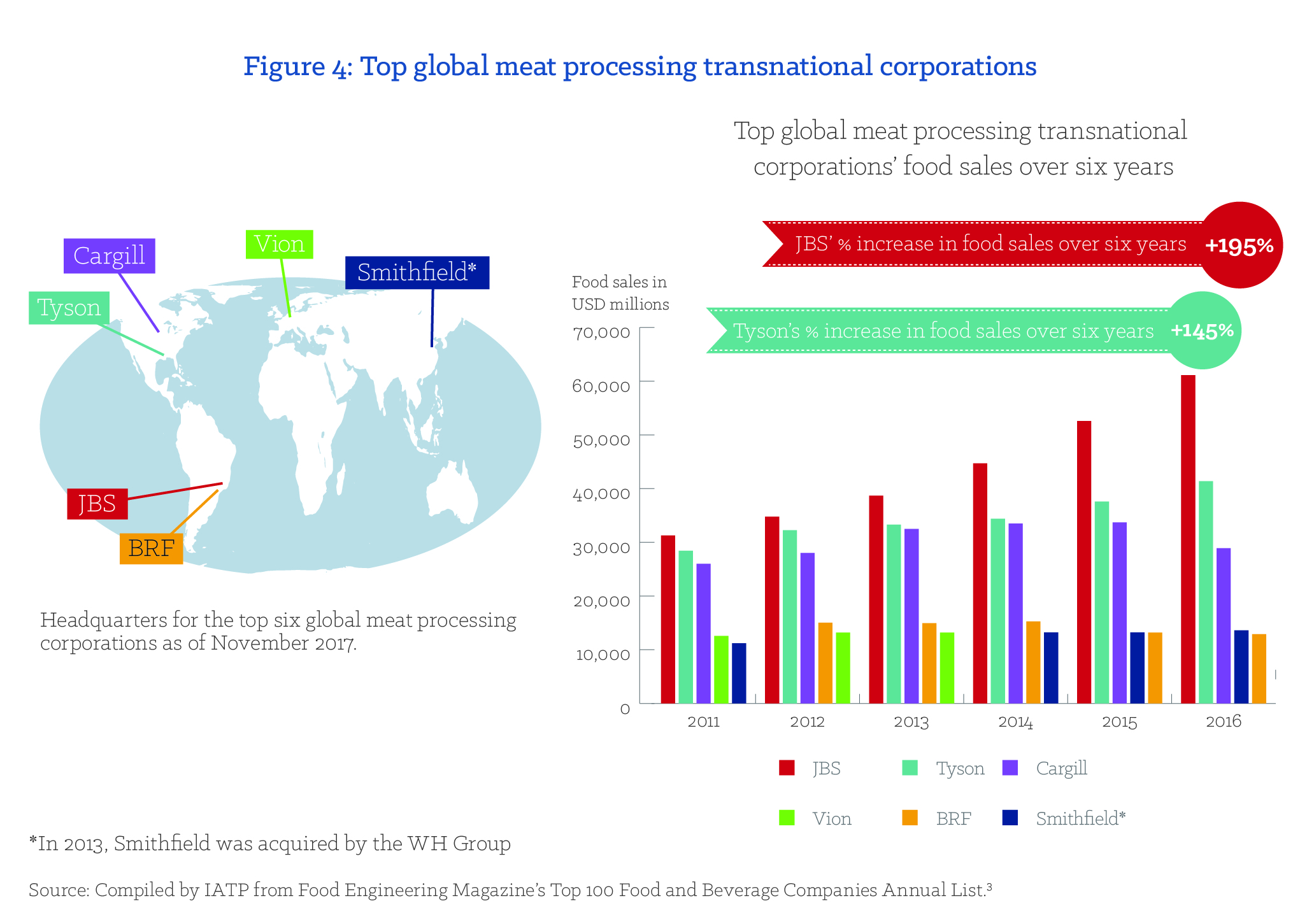

Becoming a leader of the global meat complex has come with a stark increase in the concentration of power to a handful of transnational corporations (TNCs) at every step of the Brazilian meat production chain. This has been achieved in a short span of time—since the turn of this century—and consolidated in just the last ten years.

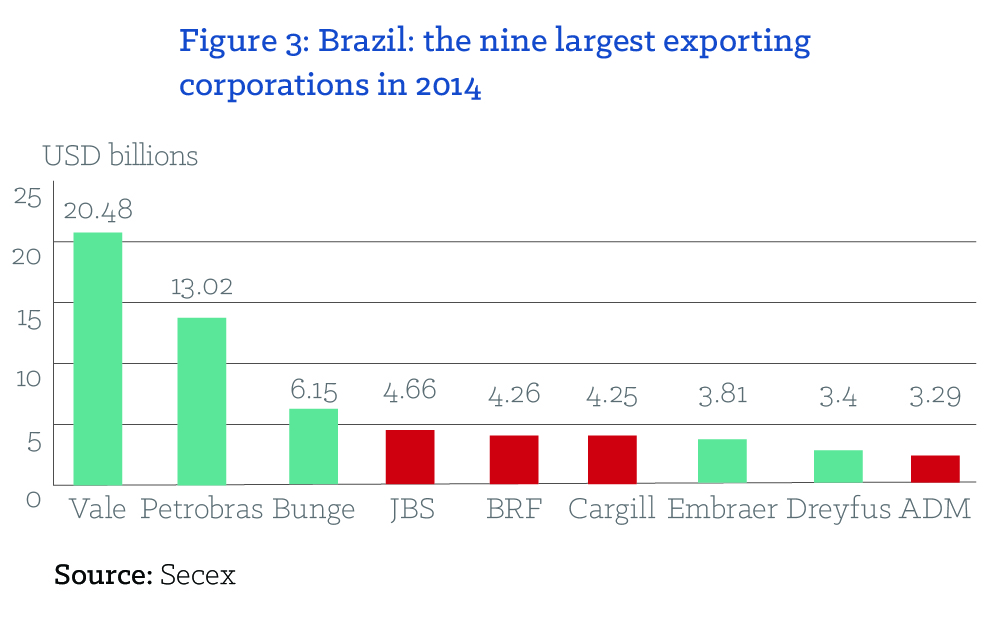

As Figure 3 illustrates, six of the nine largest exporting companies in 2014 were grain traders and meat packers. The other three, Vale, Petrobras and Embraer, are mining, oil and aeronautical industry giants, respectively. The rise of the meat industry has come with the help of the Brazilian government.

Brazil’s “National Champions” and the role of the Brazilian National Development Bank

From 2007 to 2013, the Brazilian National Development Bank (Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social [BNDES]) implemented the so-called National Champions policy. The idea was to select Brazilian exporting companies and transform them into large transnational corporations that bring home large revenues. The beneficiaries, which included some of the largest Brazilian meatpacking corporations as well as oil and mining corporations, absorbed two-thirds of the allocated BNDES resources. These “champions” included JBS-Friboi (known globally as JBS), Marfrig and Brasil Foods (BRF). These companies received large volumes of resources, not only through subsidized loans, but also through the purchasing of debentures and company shares through BNDES’s investment arm, BNDES Participações (BNDESPar). For instance, BNDESPar owns close to 25 percent of JBS’s capital while the Brazilian public bank Caixa Econômica Federal owns 10 percent.

Frequent mergers and acquisitions and consolidation across several meat segments (beef, pork, poultry, etc.) and other parts of the value chain (feed, additives) are key to the meat industry’s strategy in increasing profits. In this way, the companies used a large portion of BNDES resources to swallow up small businesses. They continued to rapidly amass power through further mergers and acquisition activities in key meat producing and consuming countries.

Brazil’s trade policy already contributes to a path of dependency on exporting land-based, natural resource intensive commodities and importing much more expensive, value-added products with a high technology content. BNDES’ use of public resources to exacerbate this trend makes little sense to many Brazilian civil society organizations (CSOs). While the National Champions policy has delivered massive profits to chief executives and shareholders of major corporations, many feel that taxpayers have gained little from large sums of public money being diverted to these large conglomerates.4 Instead, their dramatic increase in economic and political might has enabled them to operate above the law. For instance, last year, JBS chairman Joseley Batista was charged with corruption by Brazil’s independent public prosecutor in connection to JBS’ holding company, J&F Investimentos SA. In February of this year, federal prosecutors mandated that Batista’s assets be frozen in connection to fraud related to J&F’s involvement with state owned pension funds.5 Things continued to get worse in the course of the year (see Tainted meat and reputations).

JBS

JBS’ value jumped from USD 1 billion in 2004 to USD 34 billion in 2014, as it expanded from beef to poultry and other products.6 JBS now boasts of owning 340 operations that produce products ranging from meat and leather to biodiesel and metal packaging and cleaning.7 It is the world’s largest exporter of meat, selling to over 150 countries. In the U.S., it is the leading processor of beef, pork and lamb and the second largest poultry producer; it is also the leading beef producer in Canada and the largest cattle-feeder in the world.8 It additionally has operations in Argentina, Australia, Mexico, Paraguay and Uruguay.

JBS, in particular, has mastered the art of growth through mergers and acquisitions. In 2013, JBS acquired Seara, the second largest chicken and pork processing company in Brazil. Previously, Marfrig had bought it from Cargill in 2009. In 2015, JBS bought Cargill’s largest pork facility in the U.S., and in Europe, it acquired Moy Park, one of the largest European poultry and processed food facilities that belonged to Marfrig.9 In Brazil, it also acquired the French subsidiary Frangosul (owned by Doux) and the U.S. subsidiary Tyson Brazil (from Tyson Foods).10 JBS’ expansion into other exporting countries has allowed the company to avoid food safety restrictions imposed on Brazilian exports—also known as “non-tariff barriers” or sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) restrictions. Frequent outbreaks of Foot and Mouth Disease and other zoonotic diseases in Brazil continue to impose barriers on Brazilian exports. As JBS’s foreign investments have grown, such as in the U.S. and Australia, it has allowed the company 50 percent of the world market that would have otherwise remained closed had it remained only in Brazil.

BRF

Corporate concentration in the Brazilian poultry processing sector increased significantly when BNDES financed the merger of two Brazilian giants in the meat processing and frozen foods sector, Sadia and Perdigão, in 2009. Pension funds of two large state enterprises—Petrobras Social Security Foundation (12.49 percent) and the Banco do Brasil Employees’ Pension Fund (10.94 percent)—are BRF’s largest shareholders.

The company is now the largest international exporter of chicken (20 percent of global exports and nine percent of global trade in animal protein) and the seventh largest food corporation in the world, according to its annual report.16 Unlike JBS, BRF’s key strategy entails the acquisition of small companies in emerging economies that have significant potential for increasing meat consumption.

BRF owns Plusfood in Europe—a poultry processor with plants in England and the Netherlands that sells to major supermarkets in Europe.17 In 2014, the company expanded its processing plants in Argentina, which now produce poultry, margarine, cheese and beef.18

Its recent acquisitions in the Middle East and Turkey have also allowed it to become a major processor of halal meat for Islamic markets. In January, BRF consolidated its production of halal meat destined for Islamic countries under a new subsidiary in Dubai called OneFoods. This includes transferring the assets of eight slaughterhouses in Brazil that must export using halal production standards along with grain storage facilities, chicken hatcheries and feedmills.19 One of the first actions of this new subsidiary was to acquire a 60 percent stake in Banvit, Turkey’s largest poultry processing company. The Qatar Investment Authority (a Qatari Sovereign Wealth Fund) will own the remaining 40 percent.20

Marfrig

Marfrig states that it is the second largest beef operator in Brazil, the largest beef processing company in Uruguay, and the largest importer of meat in Chile. With a physical presence in 12 countries and its processed products in over a 100, the company boasts of processing up to 3.8 million head of cattle and 2.3 million head of sheep a year.21 Through its ownership of Keystone—one of the largest international suppliers of industrialized foods to large restaurant and retail chains such as McDonald’s, Subway and Wendy’s—it also processes 250 million birds and manufactures 580 thousand tons of food every year.22

Conclusion

The Brazilian government’s initiative to create National Champions has undoubtedly helped JBS, BRF and other corporations rise to the top of the global meat complex. It is also clear that this support has led to enormous profits for the CEOs and shareholders of these companies. From an economic development perspective, there is no compelling evidence that the capital used to acquire meat processing companies abroad and the resulting profits has benefited Brazilian citizens. Moreover, as we shall see in the following sections, the rest of the Brazilian population—as well as others around the globe—have been forced to bear the social and environmental costs of their rise.

To continue reading, download the full report.

Read the executive summary.

Baixe o resumo executivo em português. (Download the executive summary in Portuguese.)

Laden Sie eine deutsche Übersetzung einer früheren Version der Zusammenfassung vom April 2017 herunter. (Download a German translation of an early version of the executive summary from April 2017.)