The recent announcement that China would impose steep tariffs on imports of U.S. sorghum threw that grain’s market into turmoil. Several ships bound for China turned around and headed to other ports, forced to sell their goods elsewhere at plummeting prices. Then earlier this month, as Chinese and U.S. officials were meeting in Washington, DC over a range of trade disputes, China abruptly canceled the sorghum tariffs, leaving markets unsettled and the original question of dumping unresolved. Some ships turned back towards China.

While the announcement that the tariff would be a staggering 178.6% came as something of a shock, it wasn’t totally out of the blue. It resulted from a Chinese investigation into allegations of dumping announced earlier this year. This is just the latest salvo in what may be an escalating round of trade disputes with China, Japan and potentially other countries – with agricultural goods often caught up in larger disputes. But, beyond the erratic market signals, is agriculture export dumping a legitimate concern? What does this mean for farmers? And what does it tell us about the need to reexamine trade and agriculture policies?

Sorghum (also known as milo) is an ancient grain, with archeological evidence of its cultivation dating back to 8000 BC. Grain sorghum is not commonly consumed in U.S., but it is a staple of many African and Indian cuisines. Still, U.S. cultivation has been increasing over the last few years. In part, this is because of the benefits of including sorghum in crop rotation. It is also drought resistant, a growing value in the states where cultivation is increasing. Thirdly, it is due to a sharp increase in global demand, especially from China.

After years of relatively small levels of U.S. production and exports, in 2013, China started to import sorghum from the U.S. as a complement to corn and soy for animal feed. According to data from USDA’s Economic Research Service, starting from zero in 2012, the value of U.S. sorghum exports to China increased to $95 million in 2013, and then to $1.5 billion in 2014 and $2.1 billion in 2015, before plunging to $836 million in 2017. Even after that decrease, 81 percent of U.S. sorghum exports were destined for China last year. After the April decision to impose tariffs, much of the sorghum was diverted to other countries or for other uses (such as biofuels). Despite the cancelation of the Chinese tariff, it’s safe to say that the figure for US sorghum exports to China in 2018 will once again be closer to zero.

In hindsight, sorghum was always destined to be a fragile export market. China had increased its usage of sorghum to compensate for rising corn and wheat prices following the 2011 drought. As prices for those animal feed inputs stabilized – and then plummeted over the next few years – China’s imports also slowly decreased. That kind of ebb and flow of demand for complementary grains is not surprising, but the sudden imposition of tariffs was a shock.

China began its investigation into U.S. dumping of sorghum in February. It seems likely that the selection of sorghum was at least partially politically motivated, as most U.S. grain sorghum is produced in Kansas (home of Senate Agriculture Committee Chair Pat Roberts) and Texas (home of House Agriculture Committee Chair Mike Conaway). China had announced that it was considering antidumping tariffs for soybeans and meat, two commodities that are orders of magnitude more important than sorghum. Those tariffs are on hold for now, but they’re still a real threat to U.S. exports, especially as conflicts heat up over other issues such as China’s failure to respect international intellectual property law or the U.S. imposition of tariffs on steel. These kinds of disputes would normally be settled at the World Trade Organization (WTO), but even as it continues to bring complaints about other countries’ implementation of the WTO agreements, the Trump administration has jeopardized the functioning of the WTO dispute resolution process by refusing to renew the membership of its appellate body.

While China’s challenge to sorghum dumping is undoubtedly related to the larger trade fight with the U.S., it doesn’t necessarily mean that China is wrong about U.S. agricultural policies. Dumping is the practice of exporting goods at prices lower than the cost of production. It is widely considered an unfair way for agribusiness companies to gain foreign market share, but it also can be indicative of market problems for farmers. In this case, U.S. farmers who are being paid below cost of production prices.

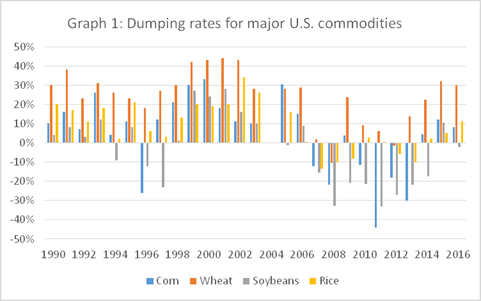

IATP has used WTO formulas to document the systematic dumping of U.S.-grown agricultural commodities (specifically wheat, soybeans, corn, and rice) for two decades. We start with USDA estimates of the cost of production to farmers, then add government subsidies attributable to each crop and an estimate of transportation costs. We then compare that number to the export price.

According to our calculations, as of 2016, U.S. wheat was exported at 30 percent less than the cost of production, corn at 8 percent less, and rice at 11 percent less. It’s worth noting that dumping rates vanish during periods of high prices like the food price crisis in 2007-2008 or the 2012 drought. However, looking at the last 20 years, dumping of U.S. farm goods is the norm, rather than the exception. Over the last few years, dumping has resumed for many U.S. crops as prices dropped once again.

IATP calculations based on cost of production and price data from USDA Economic Research Service and government subsidies from OECD Producer Support Estimates. For more information, see Counting the Costs of Agricultural Dumping, by Sophia Murphy and Karen Hansen-Kuhn.

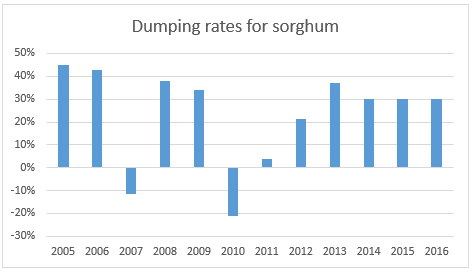

Using that same methodology, we took a look at sorghum. While not enough to justify 178.6% tariffs, dumping levels are quite high, in fact, higher than most other grains we have looked at.

Dumping by global agribusiness companies is harmful for farmers in the global North and South. It is the logical result of U.S. agriculture and trade policies that encourage overproduction, using export markets as an escape valve for falling prices and revenues. The programs and incentives in the Farm Bill, along with trade policy that focuses narrowly on opening markets create the conditions for dumping. Perhaps the best-known example of the harms caused by dumping is in Mexico, where a 400 percent increase in U.S. corn exports following NAFTA’s implementation led to more than two million Mexican farmers being driven off their land.

Less visibly, dumping also worsens incomes and increases inequality within rural America. The biggest winners from dumping are the handful of agricultural commodity trading corporations that dominate the markets. This low price, export-dependent system has left U.S. farmers with four straight years of low incomes, rising debt and increasing uncertainty.

In this case, the central issue is not Chinese farmers being driven off their lands by U.S. sorghum dumping. China produces much more of its own sorghum than it imports. It is rather that low price, export-focused markets have once again let farmers down. As Congress reconsiders the Farm Bill in the next few months, and the U.S. and China work through their very real trade disputes, the focus should shift toward supporting more stable markets, with fair prices, that support resilient and sustainable production, instead of chasing the latest fad in global markets.