- Dramatic increases in agricultural use of chemicals and fertilizers and growing concentration of livestock production since the 1980s, linked to increasing farm size and the shift from family farms to larger corporate agribusiness, have worsened water pollution.

- A majority of waterways are unsuitable for aquatic life and/or human uses, and drinking water wells, particularly in rural areas, are also contaminated.

- The laws intended to control pollution from agriculture are weak both as written and as implemented, with powerful farm and agribusiness interests effectively blocking protective standards and effective enforcement.

Agricultural trends

During the farm crisis of the 1980s, it began to be recognized that low farmgate prices, increasing corporate control of agriculture and absentee investors all contributed to farming practices that degraded the environment. These trends have only accelerated in the subsequent 30 years. Dramatic increases in the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizer, as well as factory farms producing massive amounts of manure, have degraded the nation’s surface waters, aquifers, bays and estuaries.

Nationally, nitrogen from fertilizer used on farms doubled between the late 1960s and 2015, a nearly 30-fold increase from the early 1940s to 2015. Acreage with chemical applications (pesticides, herbicides, nematicides, and chemicals used to control growth or ripen fruit) increased 7% from 2012 to 2017,1 even though the number of farms using these chemicals dropped, suggesting that larger farms have increased their usage.2 From 1992 to 2012 the use of the herbicide glyphosate increased dramatically, with at least half the country showing large increases.3

Since the 1990s there has been an extreme shift to industrialized farming, generating massive volumes of manure, in the central and southeastern U.S. in particular. In North Carolina, the state with the second largest production of hogs and pigs, the number of these animals nearly doubled between 1992 and 1997.4 Nationally, there are more than 18,000 large (1,000 animals or more) animal feeding operations out of 450,000.5

Agriculture is a primary cause of poor water quality

In 2016, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported that nationally, 71% of assessed lakes, ponds and reservoirs, 53% of assessed rivers and streams, and 80% of assessed bays and estuaries did not meet water quality standards.6 The most significant contributor to biologically impaired water quality is nutrient pollution, with 40% of stream and river miles having excessive levels of nitrogen and phosphorus resulting in algal blooms, low levels of oxygen and harm to aquatic life.

Nutrient contamination is directly linked to agricultural sources, including runoff from farm fields fertilized with chemicals or manure, and from animal feeding operations. Water quality data from 1992 to 2004 found elevated nutrient concentrations in both streams and groundwater in basins with significant agricultural development, and contamination rates increased over the study period.7 Concentrations in streams routinely were 2 to 10 times greater than safe for aquatic life, and nitrogen also exceeded federally-set human health standards in many shallow domestic wells in agricultural areas.

Contaminants from feedlots enter waterways through multiple pathways: leakage from poorly constructed manure lagoons, major precipitation events causing overflow of lagoons and runoff from recent applications of waste to farm fields, or atmospheric deposition.8 Besides nutrients, contaminants present in livestock wastes include pathogens, veterinary pharmaceuticals including antibiotics, toxic chemicals such as Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and heavy metals.9

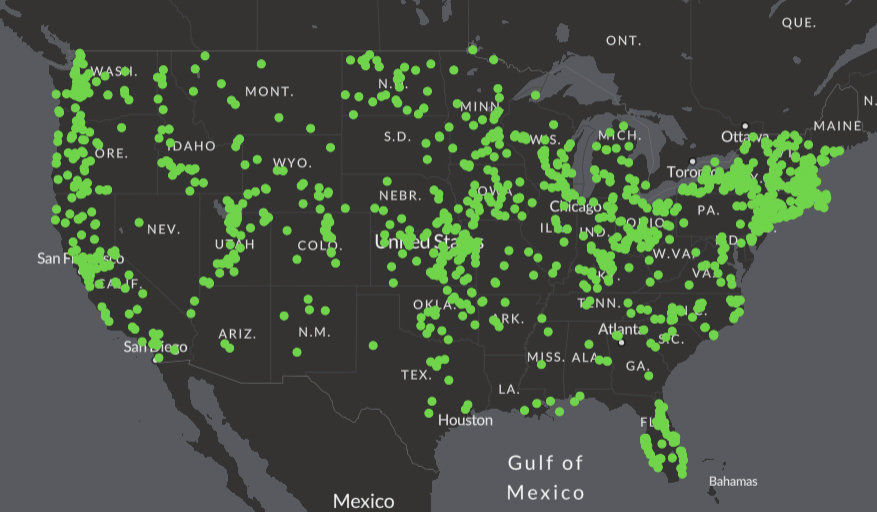

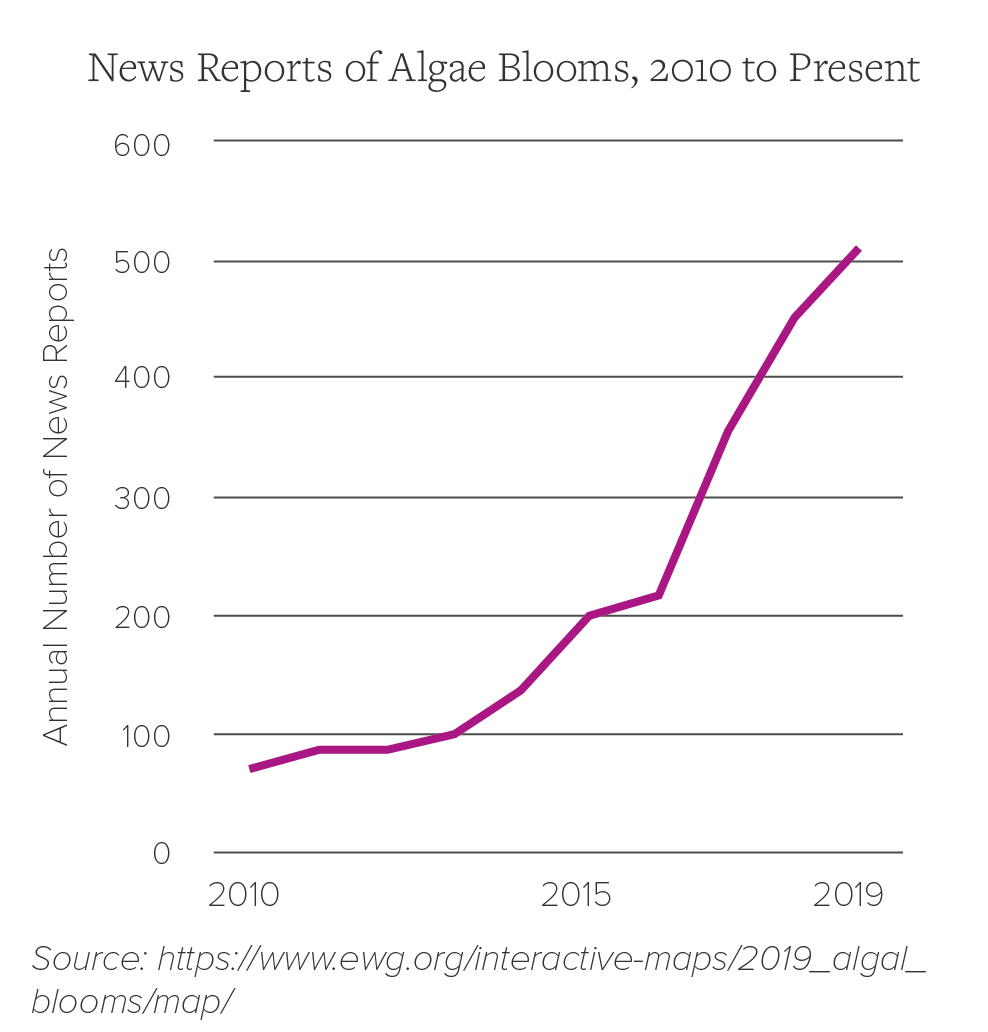

Agricultural nutrient runoff is causing algal blooms that produce extremely dangerous toxins that can sicken or kill people and animals and create “dead zones” in fresh, salt and brackish water.10 All 50 states have experienced toxic algal blooms, and there has been a dramatic increase in their incidence since 2010, believed to be fueled in part by climate change.11 The second largest algal dead zone in the world is in the northern Gulf of Mexico12 — fed by manure- and fertilizer-rich waters of the Mississippi River draining Midwestern agricultural lands — in 2017 was about the size of New Jersey.13

Agricultural pesticides also contaminate the nation’s waterways.14 Data from 1992-2001 found pesticides typically present throughout most of the year in streams draining watersheds with substantial agricultural areas.15 A comprehensive 2013 study of streams in 11 Midwestern states detected more than 180 pesticides and their byproducts.16

Public health is at stake. A U.S. Geological Survey study of private drinking wells found 23% contaminated in some way.17 Rural communities and farming areas that rely on shallow groundwater wells are especially at risk from agricultural pollutants. Wisconsin and Iowa are among many states facing a rural water contamination crisis caused by chemical fertilizers, manure, contaminated sewage sludge, and pesticides.18

A broken system that values agribusiness over clean water

Enacted in 1972, the federal Clean Water Act (CWA) was intended to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of [U.S.] waters,” with the twin goals of achieving fishable and swimmable ambient water quality throughout the U.S. by 1983, and eliminating discharges of pollutants into U.S. waters by 1985.19 More than forty years later, these goals are far from being met, and the institutional failure to control agricultural pollutants is a major reason why. This failure is both in the design of the law and in its implementation, which has consistently been thwarted by the powerful agribusiness lobby.

The CWA’s point source program requires permits, reporting, and pretreatment for industrial wastes. While meat processing facilities are legally subject to these requirements, large operations often ignore permit limits without facing any consequences.20 Enforcement is inadequate, with companies obstructing inspections or regulators failing to act.21 In the absence of federal or state enforcement, Food & Water Watch is suing a slaughterhouse that processes animal fat, meat, pathogens, ammonia and excrement that is maintained by JBS USA and the Swift Beef Company in Greeley, Colorado for failing to meet toxicity testing standards, unpermitted discharges of total suspended solids and ammonia nitrogen, and failing to report violations.22

Other significant agricultural point sources, notably industrial-scale concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), are even more loosely regulated.23 EPA requires permits only for the largest operations discharging manure directly into designated waterways, and has exempted waste stored in lagoons and disposed of through application to cropland.24 In 1987 Congress exempted from regulation “agricultural stormwater discharges” including weather-triggered leaks from manure pits. Feeding operations have been granted significant discretion to determine whether they are required to apply for a permit, and in 2012 the agribusiness lobby forced the withdrawal of regulations to create a central database of basic CAFO information.25 In violation of the law, regulations in some of the 38 states with delegated water pollution permit-writing authority fail to meet even the weak federal minimum standards, and some states with large numbers of CAFOs do not require permits for the vast majority of these operations. Nationally, only an estimated 41% of CAFOs that EPA says should have water pollution discharge permits actually have them.26

The CWA provisions regulating nonpoint sources — such as runoff from agricultural fields — are even less effective, and do not give EPA express authority to mandate standards. Congress left it to individual states to decide how best to control pollution from nonpoint sources, and most continue to do so entirely through voluntary programs such as education and financial assistance.27

The human impact of the dramatic increase in industrial agriculture, and the failure to regulate the heavy load of pollutants it generates, falls disproportionately on poor, rural and minority communities.28 The clustering of hog CAFOs in low-income, minority communities in North Carolina in particular has raised concerns of environmental injustice and environmental racism.29

Unfortunately, the rural pollution crisis is about to get even worse. Recent changes to the definition of “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) adopted by the Trump administration in 2019 will significantly limit the scope of the CWA, removing environmental protections from millions of miles of streams and roughly half of the country’s wetlands, further limiting control of runoff from manure, fertilizers and pesticides.30 This, too, is the direct result of agribusiness lobbying, as USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue made clear in announcing the change: “Repealing the WOTUS rule is a major win for American agriculture.”31

Endnotes

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Census, Table 46. Fertilizers and Chemicals Applied: 2017 and 2012, https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/st99_1_0045_0046.pdf.

- National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition Blog, 2017 CENSUS OF AGRICULTURE DRILLDOWN: CONSERVATION AND ENERGY, June 19, 2019, http://sustainableagriculture.net/blog/2017-census-of-agriculture-drilldown-conservation-and-energy/http://sustainableagriculture.net/blog/2017-census-of-agriculture-drilldown-conservation-and-energy/.

- James A. Falcone, Jennifer C. Murphy & Lori A. Sprague (2018) Regional patterns of anthropogenic influences on streams and rivers in the conterminous United States, from the early 1970s to 2012, Journal of Land Use Science, 13:6, 585-614, DOI: 10.1080/1747423X.2019.1590473, at p.603, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1747423X.2019.1590473?scroll=top&needAccess=true (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Dubrovsky, N.M., Burow, K.R., Clark, G.M., Gronberg, J.M., Hamilton P.A., Hitt, K.J., Mueller, D.K., Munn, M.D., Nolan, B.T., Puckett, L.J., Rupert, M.G., Short, T.M., Spahr, N.E., Sprague, L.A., and Wilber, W.G., 2010, The quality of our Nation’s waters—Nutrients in the Nation’s streams and groundwater, 1992–2004: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1350, (citing National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2008), https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1350/pdf/circ1350.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Inspector General Report, Eleven Years After Agreement, EPA Has Not Developed Reliable Emission Estimation Methods to Determine Whether Animal Feeding Operations Comply With Clean Air Act and Other Statutes, Report No. 17-P-0396, September 19, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-09/documents/_epaoig_20170919-17-p-0396.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “National Summary of State Information” in Water Quality Assessment and TMDL Information, http://ofmpub.epa.gov/waters10/attains_nation_cy.control (accessed September 13, 2019). Note that the most recent data reflected in EPA’s assessment is from 2016, but data dating back to 2008 is also included, https://ofmpub.epa.gov/waters10/attains_nation_cy.control#status_of_data (accessed September 13, 2019). Note that the most recent data reflected in EPA’s assessment is from 2016, but data dating back to 2008 is also included, https://ofmpub.epa.gov/waters10/attains_nation_cy.control#status_of_data.

- Id, Dubrobsky et al, https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1350.

- JoAnn Burkholder, Bob Libra, Peter Weyer, Susan Heathcote, Dana Kolpin, Peter S. Thorne, and Michael Wichman, “Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations on Water Quality,’ Environ Health Perspect. 2007 Feb; 115(2): 308–312. Published online 2006 Nov 14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8839 PMCID: PMC1817674 PMID: 17384784, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1817674/ (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Sharon Lerner, “Toxic PFAS Chemicals Found in Maine Farms Fertilized with Sewage Sludge”, The Intercept, June 7 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/06/07/pfas-chemicals-maine-sludge/ (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020)

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA website, Nutrient Pollution - Harmful Algal Blooms, https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/harmful-algal-blooms (accessed January 30, 2020). See also U.S. Center for Disease Control, https://www.cdc.gov/habs/index.html (accessed January 30, 2020). (accessed January 30, 2020). See also U.S. Center for Disease Control, (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Environmental Working Group, Website, Toxic Algae: https://www.ewg.org/key-issues/water/toxicalgae (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, Department of Commerce, Ocean Today: Happening Now: Dead Zone in the Gulf 2017, https://oceantoday.noaa.gov/happnowdeadzone/ (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Osterman, L.E., Poore, R.Z., Swarzenski, P.W., 2008, Gulf of Mexico dead zone–1000 year record: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1099, https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1099/ (January 30, 2020) (January 30, 2020).

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Pesticide National Synthesis Project, Estimated Annual Agricultural Pesticide Use, https://water.usgs.gov/nawqa/pnsp/usage/maps/about.php (accessed January 30, 2020). USGS tracks specific pesticide product use and trends by watershed and county and has estimated data through 2016, with data maps available online through 2012 but limited analysis of that data. (accessed January 30, 2020). USGS tracks specific pesticide product use and trends by watershed and county and has estimated data through 2016, with data maps available online through 2012 but limited analysis of that data.

- USGS, Pesticides in the Nation’s Streams and Ground Water, 1992–2001—A Summary (March 2006) https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2006/3028/, (accessed January 30, 2020). USGS has screened more than 185 million water-quality records from over 600 Federal, State, Tribal, and local organizations as part of an assessment showing stream trends in water chemistry (nutrients, pesticides, sediment, carbon, and salinity) and aquatic ecology (fish, invertebrates, and algae) for: 1972-2012, 1982-2012, 1992-2012, and 2002-2012 at https://nawqatrends.wim.usgs.gov/swtrends/, (accessed January 30, 2020). USGS has screened more than 185 million water-quality records from over 600 Federal, State, Tribal, and local organizations as part of an assessment showing stream trends in water chemistry (nutrients, pesticides, sediment, carbon, and salinity) and aquatic ecology (fish, invertebrates, and algae) for: 1972-2012, 1982-2012, 1992-2012, and 2002-2012 at https://nawqatrends.wim.usgs.gov/swtrends/.

- USEPA, “Data Show Pesticides Prevalent in Midwestern Streams,” Nonpoint source news and notes, March 2018 (publication now discontinued), https://www.epa.gov/nps/nonpoint-source-news-notes (last accessed September 13, 2019), quoting from “Complex mixtures of dissolved pesticides show potential aquatic toxicity in a synoptic study of Midwestern U.S. streams,” https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.156 (last accessed September 13, 2019), quoting from “Complex mixtures of dissolved pesticides show potential aquatic toxicity in a synoptic study of Midwestern U.S. streams.”

- USGS website, Contamination in U.S. Private Wells, https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/contamination-us-private-wells?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects. https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/contamination-us-private-wells?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects (accessed January 30, 2020). Some of the detected pollutants are naturally occurring, such as arsenic and radon.

- Jack Healy, “Rural America’s Own Private Flint: Polluted Water Too Dangerous to Drink”, New York Times, November 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/03/us/water-contaminated-rural-america.html

- Clean Water Act and amendments, 33 U.S.C. §1251 et seq. (1972). USEPA website, Laws & Regulations, Summary of the Clean Water Act, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Joseph Cotruvo, “Wastewater Treatment Challenges in Food Processing and Agriculture,” Water Technology, August 31, 2018, https://www.watertechonline.com/wastewater-treatment-challenges-food-processing-agriculture/ https://www.watertechonline.com/wastewater-treatment-challenges-food-processing-agriculture/ (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Southern Environmental Law Center, “Hog producers deny access to pollution monitors, violate agreement,” October 14, 2015, https://www.southernenvironment.org/news-and-press/news-feed/hog-farmers-deny-access-to-pollution-monitors-violate-agreement (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Notice of Intent Filed to Sue Over Chronic Water Pollution From Colorado Slaughterhouses, Food and Water Watch, January 31, 2019, https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/news/notice-intent-filed-sue-over-chronic-water-pollution-colorado-slaughterhouses (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020)

- USEPA, “National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)”, EPA, Animal Feeding Operations, https://www.epa.gov/npdes/animal-feeding-operations-afos (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Brett Walton, WaterNews, EPA Turns Away from CAFO Water Pollution, December 22, 2016, https://www.circleofblue.org/2016/water-policy-politics/epa-turns-away-cafo-water-pollution (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- “The EPA’s Failure to Track Factory Farms”, Food and Water Watch Issue Brief, August 2013, https://www.scribd.com/document/163773083/The-EPA-s-Failure-to-Track-Factory-Farms (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Sharon Treat and Shefali Sharma, “Selling Off the Farm: Corporate Meat’s Takeover Through TTIP”, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, July 2016, at p.39 (accessed January 30, 2020)

- Robert W. Adler, “CPR Perspective: Nonpoint Source Pollution TMDLs, Nonpoint Source Pollution, and the Goals of the Clean Water Act,” Center for Progressive Reform, http://www.progressivereform.org/perspTMDLs.cfm (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Erica Hellerstein and Ken Fine, “A million tons of feces and an unbearable stench: life near industrial pig farms”, The Guardian, September 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/sep/20/north-carolina-hog-industry-pig-farms (accessed January 30, 2020) (accessed January 30, 2020).

- Wendee Nichol, “CAFOs and Environmental Justice: The Case of North Carolina,” Environ Health Perspect. 2013 Jun; 121(6): a182–a189, published online 2013 Jun 1. doi: 10.1289/ehp.121-a182, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3672924/ (accessed January 30, 2020). This article has been corrected. See Environ Health Perspect. 2013 July 01; 121(7): a210. (accessed January 30, 2020). This article has been corrected. See Environ Health Perspect. 2013 July 01; 121(7): a210.

- Annie Snider, “Trump set to gut water protections,” Politico, January 14, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/01/14/trump-water-regulation-rollback-099016.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Secretary Perdue Statement on EPA WOTUS Announcement, September 12, 2019, https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2019/09/12/secretary-perdue-statement-epa-wotus-announcement. The Trump administration has misleadingly characterized the rollback as a “recodification of pre-existing rules”, USEPA, Navigable Waters Protection Rule, https://www.epa.gov/nwpr/definition-waters-united-states-recodification-pre-existing-rules (accessed January 20, 2020). The Trump administration has misleadingly characterized the rollback as a “recodification of pre-existing rules”, USEPA, Navigable Waters Protection Rule, https://www.epa.gov/nwpr/definition-waters-united-states-recodification-pre-existing-rules (accessed January 20, 2020).

Download the PDF.

Read the introduction and the other eight pieces in the series.