This article is part of a series highlighting work around the world to build agroecological practices, science and movements. Agroecology has emerged as a set of practices based on principles that guide how to produce food sustainably, as well as how to manage the social relationships that govern food production, processing, exchange and waste management in a fair manner.

It’s no secret that United States agricultural policy is overwhelmingly oriented to large-scale industrial agriculture. The policy imperatives embedded in the Farm Bill to “get big or get out” drove U.S. farmers to massively expand their production for export no matter how low prices dropped. This has led to an exodus of farmers out of agriculture, a dramatic rise in corporate concentration in agriculture, and increases in water and air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

This system undermines more sustainable production and rural livelihoods in other countries, as well. IATP has documented the extent of dumping, i.e., exporting farm goods at below the cost of production, since the late 1990s. With some brief exceptions, there has been a clear and consistent pattern of cheap exports invading global markets, to the detriment of farmers. As of 2020, the rates of dumping stood at 24% for wheat, 14% percent for corn and 8% for soybeans.

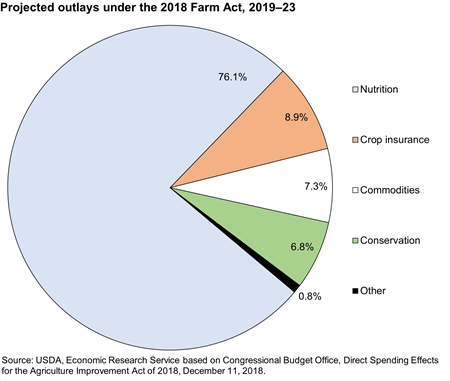

The 2018 Farm Bill authorized US$428 billion in spending over five years for 12 nutrition and agriculture programs. The amounts actually spent each year depend on the appropriations approved each year by Congress, and priorities could shift with new Farm Bills. Currently, 76% of Farm Bill spending is directed to nutrition programs for low-income people, primarily the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. About 28% of the remaining funds are directed to conservation programs. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act added another $20 billion over 10 years to conservation programs.

While the vast majority of U.S. spending on agriculture is oriented to large-scale industrial production for export, two programs within the Conservation Title of the Farm Bill represent some first steps towards agroecological production. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) supports investments by farmers in single practices that help transition to more sustainable production. The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) rewards a whole-farm approach by farmers to adopt more conservation-based systems. CSP’s whole-farm approach supports climate-resilient strategies that support soil health, water quality, perennial grasses, sustainable livestock management and cover cropping.

Working with technical advisors, farmers select the practices that make sense in their specific situations and receive financial support based on their needs. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) describes CSP as “a comprehensive working lands conservation program designed to help farmers and ranchers protect and improve natural resources and the environment on productive and profitable farms.” NSAC notes that, “More than 70 million acres of crop, forest, and pasture, and rangeland are currently enrolled in the program – accounting for nearly seven percent of farm and ranch land nationwide.”

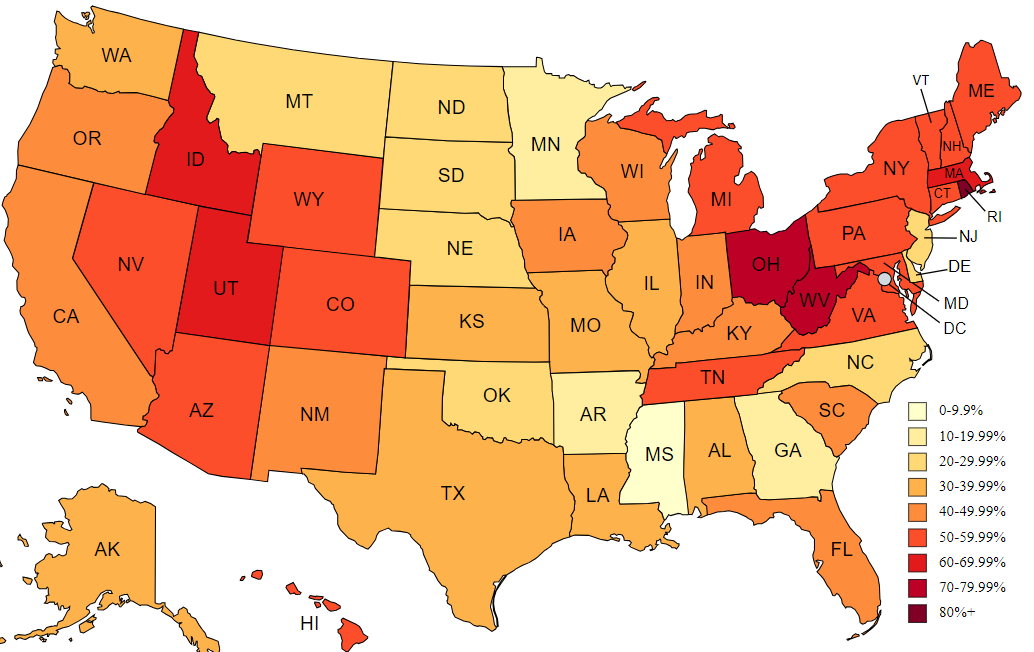

These programs are both extremely popular among farmers and chronically underfunded. As of 2022, only 24.8% of CSP applicants were awarded contracts. Many of those projects will help farmers adapt to a changing climate and improve soil health and water quality, as well as allow farms to operate in a more agroecological way. Despite an increase in the ratio of applications to contracts awarded, USDA still rejects more than three in four farmer applications to CSP. This is an improvement over 2020, when just 18.2% of CSP contracts were awarded nationwide (and with considerable variation in approval rates among states).

Percentage of CSP Applicants Awarded Contracts, FY 2023

In the case of EQIP, all too often, much of the funds are used by Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs, or factory farms) to create manure lagoons and animal mortality facilities, merely cleaning up egregious air and water pollution generated by their operations instead of transitioning to more sustainable production systems. Under current law, 50% of EQIP funding is required to go toward livestock-focused practices, and 10% of EQIP funds should benefit wildlife habitat. These percentages are nationwide; if a state such as New Hampshire cannot allocate 50% of its funding for livestock practices, that funding can be reallocated to a different state, such as Iowa, that can. While there are climate-resilient livestock practices, such as advanced grazing management and pasture improvements that provide wildlife habitat, there are also some conservation program-funded livestock practices that are anything but resilient.

CSP and EQIP are not agroecology programs, but they do represent an important and growing new direction in U.S. agriculture policy. The conservation programs are imperfect, and they are constantly under threat of funding cuts by Congress. At the same time, they have also generated new and growing support among social movements in the U.S. seeking to transition to more sustainable production, including those pushing hard for true steps toward agroecology. Many of these campaigns and the changes in public policies that result begin at the municipal and state level and build from the ground up to increase pressure for changes in national policies. There are several local foods focused programs, including urban farms, within the Farm Bill that respond to growing activism among farmers and demands by consumers for healthy foods that also build connections within their communities.

In addition to these agricultural support programs, innovative public procurement programs are helping to create markets for locally grown, sustainable food production that links farmers to schools and other public institutions. Over 67,000 schools participate in these programs, reaching more than 42 million students. These programs have been extended to early care initiatives, including those for low-income families like the public Head Start program, often incorporating educational curricula to help children learn about where their food comes from and to make connections to the people from many cultures who grow their food. In Minneapolis, for example, the Hmong American Farmers Association works with IATP and other partners to bring healthy traditional foods into Head Start and other daycare programs, teaching children about the cultural values behind the food they eat, as well as ensuring they have the healthy food they need to thrive.

Of course, locally grown does not necessarily mean sustainably grown, much less grown to achieve food justice. However, in addition to creating new markets for local farmers, these programs have inspired important state initiatives to incorporate agroecological values into those supply chains. In 2012, the Los Angeles Unified School District signed the Good Foods Purchasing Pledge, committing to guide procurement decisions according to five criteria: local economies; environmental sustainability; valued workforce; animal welfare; and nutrition. The process began in local food policy councils and has expanded across the country as social movements press for authentic changes in how decisions on food supply chains are enacted. The Center for Good Foods Purchasing (which includes the Food Chain Workers Alliance, Real Food Media, United Food and Commercial Workers, Friends of the Earth, and the Union of Concerned Scientists, among other partners) is pressing more school systems to take up and implement the pledge. Since the program began in Los Angeles, school districts in San Francisco, Oakland, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, Washington, D.C., Cincinnati, Boston and Austin have the pledge, and efforts are underway in Minneapolis, Buffalo and New York City.

The U.S. agricultural system is driven by large corporate interests, but it is not monolithic. The conservation programs in the Farm Bill, as well as creative new approaches to supply chains and fair markets, represent important first steps to open a broader public debate toward an agroecological transition.